The Falkland Islands, South Georgia & Antarctic Peninsula

Oct 18 - Nov 6 2017 (as naturalist)

Antarctica - Off The Beaten Track

Nov 6 - Nov 18 2017 (as artist in residence)

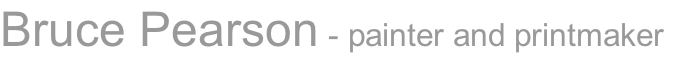

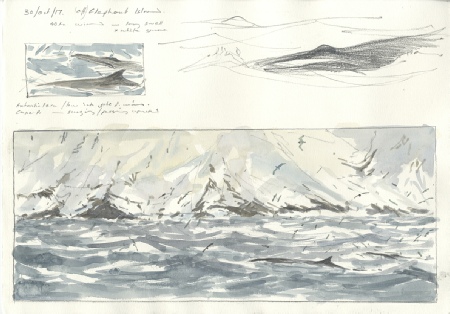

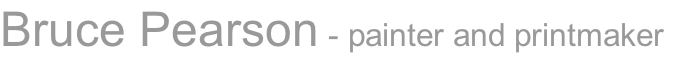

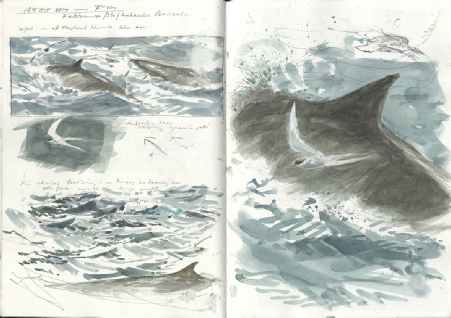

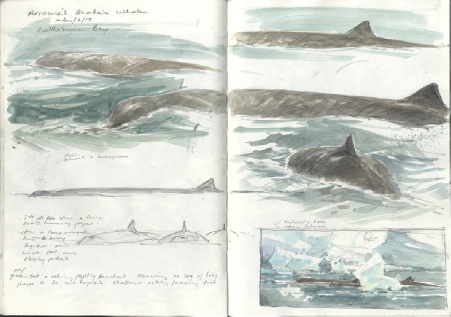

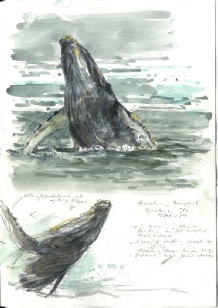

The two trips were early in the southern ocean summer season. That meant whale sightings were infrequent as many were still migrating south, so when they did surface the excitement was even greater. Especially when in Willhelmina Bay on the Antarctic Peninsula a pod of about four or five Arnoux’s beaked whales emerged very close to the small boat I was in.

Because of the dorsal fin shape and blunt rounded front end my first thought was sperm whale! But a moment later the scarring over the dorsal surface, colour of the animals and sudden sight of a beak confirmed their identity

My only ever other contact with this magnificent creature was a specimen that washed up on Bird Island in 1976 after a fierce storm and high tide stranded a whale carcass at the back of Jordan Cove.

One of the chaps reported one evening that he’d seen the huge creature when walking back from the far end of the island. There was still light enough for the rest of us to get across to Jordan Cove and take a look for ourselves and get some photographs. We decided that we’d confirm its identity and do some science in daylight the next day - we’d go down again with a tape to take measurements, pliers and a saw to get teeth and collect tissue, plus specimen jars etc, etc.

That night as we sat in the hut talking excitedly about our extraordinary find and how important to science our data would be, the storm rose again. It was even more fierce that it had been a couple of evenings earlier.

Arnoux’s beaked whale Berardius arnuxii

The biology, population and distribution of Arnoux’s beaked whale is poorly understood. It seems to occur near deep escarpments and seamounts of the southern oceans. It is known mostly from specimens and photographs of beached or stranded animals ranging from South Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, Falkland Islands, South Georgia, South Shetlands, South Africa, and Antarctic Peninsula.

They are presumed to migrate seasonally away from the edge of the ice in winter for breeding, although some have been known to become trapped by shifting ice around Antarctica, and may winter or die there.

Arnoux's beaked whales reach a known maximum size of 9.75 m. Females are probably larger than males, as is generally true in beaked whales, and a large adult can weigh as much as 8,200kg (9 tons). Length at birth is unknown, but is probably around 4 m. They are highly social animals; most groups number between 6 and 10 individuals, but some pods of 80 whales or more have been seen.

It is thought they feed mostly on squid and bottom-dwelling fish diving to at least 3,300 ft (1,000 m) with a dive lasting from 20 minutes to over an hour.

Arnoux's beaked whales are slate grey to light brown with a small head region that is generally lighter than the rest of the body. They have a moderately steep bulbous forehead with a long tube-like beak, small rounded flippers and short slightly falcate dorsal fin. The body is often heavily scarred and scratched, and the underside tends to be lighter, and covered with white blotches.

There has not been any substantial commercial hunting for this species, but some have been taken for scientific study. Arnoux's beaked whale became known to science as a result of a specimen that stranded in Akoroa Harbor, Bank Peninsula, New Zealand, and was presented to the Museum of Paris in 1846 by one M. Arnoux, surgeon to the French corvette Rhin, commanded by Captain Bérard.

The next day, laden with our scientific equipment, the four of us headed over the island to Johnson Cove. Our prize specimen had gone! There was nothing except oily stains on the storm tide line high up on the beach and a scattering of stinking fragments of fleshy detritus.

The tail end of the storm that had delivered an Arnoux’s beaked whale to our remote sub-Antarctic island had overnight taken it away again.

As artist in residence I have plenty of time to pursue my own work, but I also try to encourage anyone who eventually tires of taking photographs to just sit and draw for a while.

I always have spare paper and a few pencils with me, but some guests arrive on board with a full set of watercolours and all the proper pads and papers plus pencils, erasers and sharpeners determined to do some serious art.

No problem with that, but I tend to say that we could sit for a 100 years in the same spot with multitudes of penguins and a vast glacial and iceberg jammed landscape stretching out beyond yet still fail to make sense of it creatively unless we strip it down to its most basic elements - and we only have a couple of hours to do it!

So let’s just draw - a sheet of paper and a pencil or piece of charcoal - and start extracting the raw elements we observe around us, stripping out the inessentials and then start bolting them back together again to form a new reality. One that is personal, about an individual impression that captures a feeling for what is fundamental to the immediate experience.

As I sometimes say to the handful of guests who really engage with their drawing, the number of people who have visited Antarctica and leave with a multitude of photographs as the personal record of their voyage can be numbered in their many thousands. But those who have sat in the snow just with a sketchpad and pencil simply observing and making marks as they create a personal experience of the Antarctic reality probably number less than 100. For that reason alone your drawing is very special.

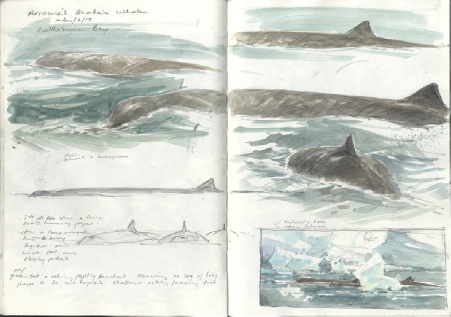

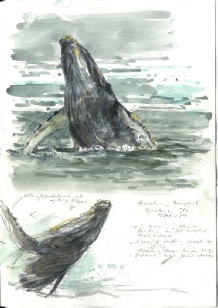

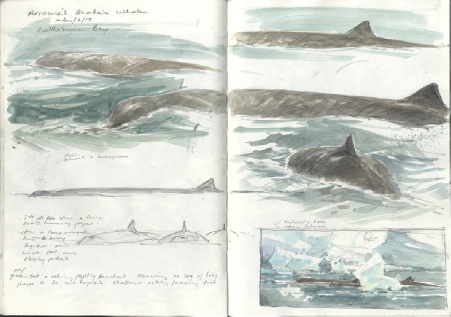

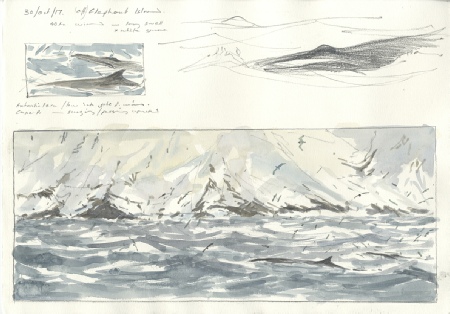

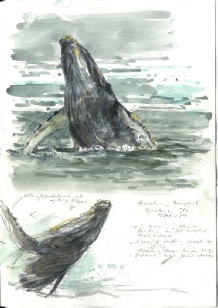

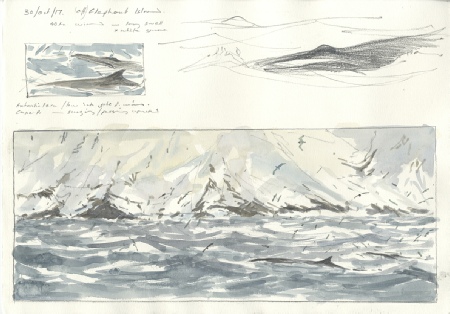

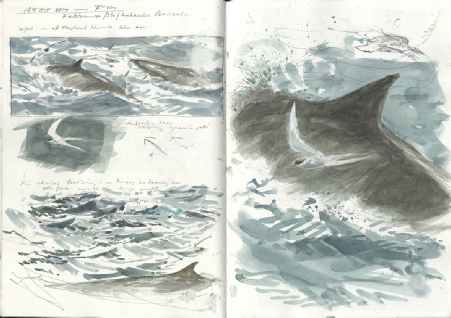

Whale sketches - mainly fin whale on A3 pages, but also a wonderful sighting of breaching humpback in the pack-Ice in an A4 sketchbook.

Some days the weather turns suddenly and we can’t get off the ship. Its then that there are opportunities to further break down the idea that the art onboard is all about painting techniques, copy photographs and painting nice pictures of Antarctica.

Instead, working together as a group on a large sheet of paper we have to think much harder about how the marks individuals make relate to those that others are making all around. Also, it helps break down the notion of possession - a corner or element completed by one is ‘better’ than another. We had great fun one afternoon in heavy seas and the group produced very interesting results.

Next season I plan on taking with me a couple of rolls of cheap plain wallpaper / lining paper and soft charcoal. When the opportunities arise I’ll lay out a long piece in the snow beneath a penguin colony and encourage anyone wanting to stop for a while and just look and draw to collaborate on a single drawing. Should be fun!

Getting on with my own work. Sketching at a chinstrap penguin colony on the Antarctic peninsula, November 2017

As ever, huge thanks to One Ocean Expeditions for their continued support and enthusiasm for having me onboard. The voyages are a great privilege and every year I value all the new and exciting opportunities they present.